Custom Bearing Design and Application in Engineering System

Home > News > Industry News > Custom Bearing Design and Application in Engineering System

Bearings—including rolling bearings and plain bearings—are fundamental mechanical components used to support rotating or reciprocating parts, carry loads, and reduce friction. In modern engineering systems, a custom bearing is not merely a standardized component but a tailored functional element that directly influences system accuracy, vibration behavior, thermal characteristics, and overall service life.

From an engineering standpoint, bearings must be considered as part of the complete shaft system and machine assembly. Bearing selection, installation, and operation must be matched to real working conditions, rather than relying solely on catalog data. Load type, rotational speed, accuracy requirements, lubrication conditions, and environmental factors all determine whether a standard bearing is sufficient or a custom bearing solution is required. In this blog post, JRZC, as a high performance bearing manufacturing company, will share insights on the features of custom bearing design and application in engineering systems.

Core Engineering Functions of Bearings

From an engineering standpoint, the function of a bearing goes far beyond simply “allowing a shaft to rotate.” Its essential roles can be summarized as follows.

Supporting Rotating Shafts or Moving Components

Bearings form a stable support structure through the interaction of inner rings, outer rings, rolling elements, or sliding surfaces, ensuring the geometric stability of the shaft system.

Carrying and Transmitting Loads

Depending on bearing design, bearings carry radial loads, axial loads, or combined loads, and transmit these forces to the housing or machine frame.

Reducing Friction and Energy Loss

Rolling bearings reduce friction by converting sliding friction into rolling friction, while plain bearings rely on an oil film to separate metal surfaces and minimize wear.

Ensuring Motion Accuracy and Operational Stability

Bearing internal precision and stiffness directly affect shaft runout, axial displacement, vibration levels, and noise during operation.

Participating in Shaft Positioning and Constraint of Degrees of Freedom

By properly arranging fixed-end and floating-end bearings, axial positioning can be controlled while accommodating thermal expansion of the shaft.

Bearing selection is essentially an engineering matching process that balances these functional requirements.

Characteristics of Major Bearing Types

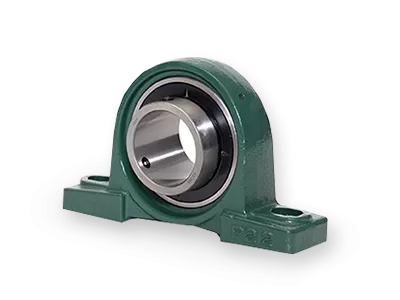

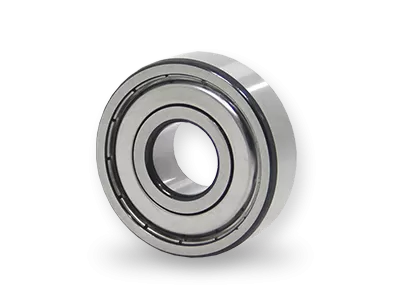

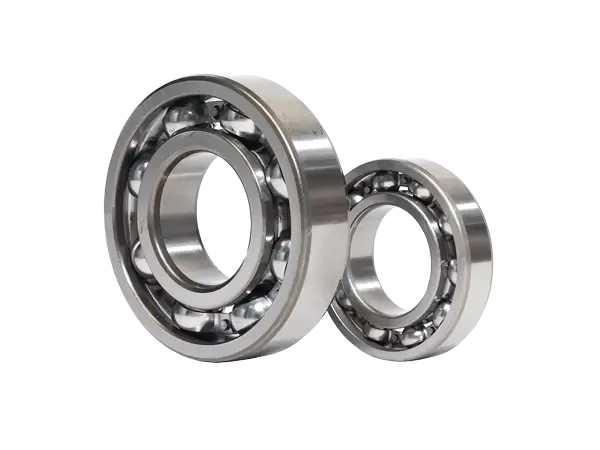

Deep Groove Ball Bearings

Typical designation: 6xxx series (e.g., 6205, 6310)

These bearings primarily carry radial loads and can withstand limited axial loads in both directions. They feature high speed capability, low friction, simple structure, and strong versatility.

They are widely used in motors, pumps, fans, household appliances, and general machinery.

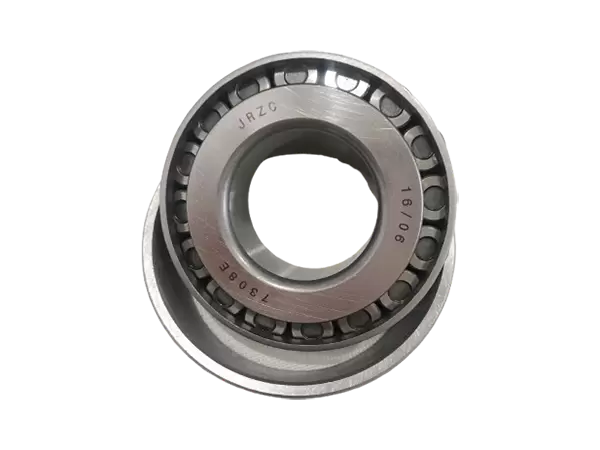

Angular Contact Ball Bearings

Typical designation: 7xxx series (e.g., 7208, 7312)

Angular contact ball bearings carry both radial loads and axial loads in one direction. The contact angle (15°, 25°, 40°, etc.) determines axial load capacity. They are usually installed in pairs or sets to carry axial loads in both directions and are suitable for high-speed, high-precision applications.

They are commonly used in machine tool spindles and high-speed rotating equipment.

Self-Aligning Ball Bearings

Typical designation: 1xxx series (e.g., 1208, 1212)

These bearings feature automatic self-aligning capability and are insensitive to misalignment between the shaft and housing. Their radial load capacity is limited, and they are not suitable for carrying large axial loads.

They are typically applied where shaft deflection is large or installation accuracy is difficult to guarantee.

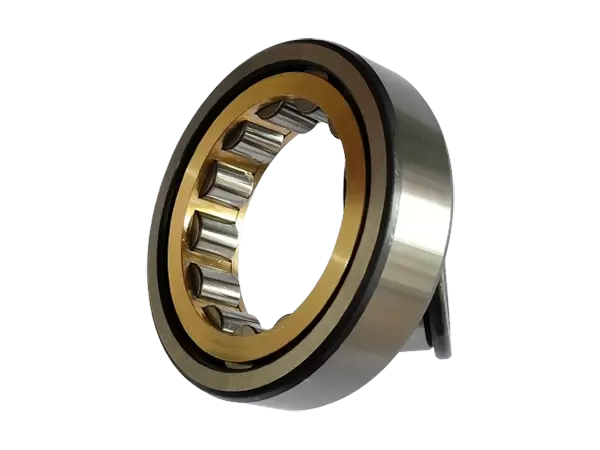

Cylindrical Roller Bearings

Typical designation: N, NU, NJ, NUP series

Cylindrical roller bearings offer high radial load capacity and high stiffness. They mainly carry radial loads, while certain structural variants can carry limited axial loads. They are suitable for medium- to high-speed heavy-load conditions.

Typical applications include motors, gearboxes, and machine tool support bearings.

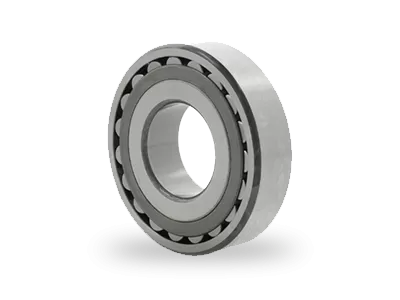

Spherical Roller Bearings

Typical designation: 2xxx and 3xxx series

These bearings can carry large radial loads and axial loads in both directions, while also providing self-aligning capability. They are well suited for heavy loads and impact conditions, although their allowable speeds are relatively low.

They are widely used in metallurgy, mining, heavy machinery, and vibrating equipment.

Thrust Bearings

Thrust ball bearings carry pure axial loads, allow relatively high speeds, but have limited axial load capacity.

Thrust roller bearings can withstand much higher axial loads and offer high stiffness, but operate at lower speeds.

They are commonly used in vertical shaft systems, screw mechanisms, turntables, and heavy axial load supports.

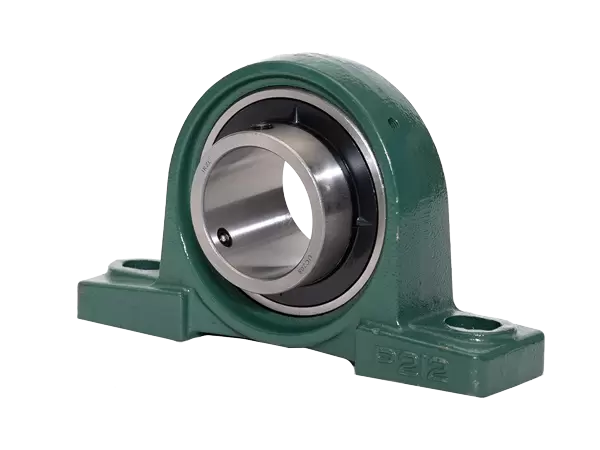

Plain Bearings

Plain bearings rely on an oil film to generate load-carrying capacity. They offer high load capacity, good impact resistance, low noise, and long service life under proper lubrication conditions. However, they place higher demands on lubrication and maintenance.

They are mainly used in engine crankshafts, large compressors, and heavy-load low-speed equipment.

Bearing Performance Attributes

Under normal design and manufacturing conditions, rolling bearings rarely fail due to material strength fracture. The dominant failure mode is contact fatigue.

Under alternating Hertzian contact stress, microcracks form on the raceways or rolling elements and gradually propagate, eventually leading to surface spalling.

Based on this failure mechanism, bearing design adopts a probabilistic life approach.

Key Parameters

Basic dynamic load rating (C)

Basic rating life (L10):

The number of revolutions or operating hours at which 90% of bearings in a group can be expected to operate without fatigue failure under specified conditions.

Whether a bearing is suitable depends on whether its calculated life meets the design requirement—not merely on whether it can withstand the applied load.

Influence of Actual Load Conditions and Shaft System Behavior

In theoretical calculations, bearing loads are typically simplified into radial load (Fr) and axial load (Fa). In real engineering systems, however, additional factors must be considered:

Load non-uniformity caused by shaft deflection

Installation misalignment and geometric errors

Load redistribution in multi-bearing support systems

Additional loads caused by thermal expansion due to temperature rise

These factors alter the load distribution among rolling elements, causing certain elements to operate under consistently higher loads, thereby reducing bearing life. In high-speed or high-stiffness systems, shaft system stiffness analysis combined with engineering experience is often required for correction.

Internal Clearance, Preload, and Operating Condition

Definition of Clearance

Radial clearance: Radial displacement of the inner ring relative to the outer ring before installation

Axial clearance: Axial displacement of the inner ring relative to the outer ring

Clearance is a functional parameter, not a manufacturing defect.

Common Clearance Classes (ISO 5753 / GB/T 4604)

C2: Smaller than standard clearance

CN / C0: Standard clearance

C3: Greater than standard clearance

C4 / C5: Larger clearances

Operating clearance = manufacturing clearance − interference fit effect − temperature difference effect

Improper clearance selection often results in abnormal temperature rise, increased noise, or premature failure.

Lubrication Condition and Bearing Life

During normal operation, rolling bearings should operate under elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL), where a stable oil film forms under high contact stress to separate metal surfaces.

Key factors influencing lubrication condition include:

Actual lubricant viscosity at operating temperature

Speed and speed factor (n·dm)

Load level

Lubrication method (grease, oil bath, circulating oil)

Contamination control level (ISO 4406)

Insufficient lubrication, contamination, or excessive grease filling are major contributors to bearing failure.

Structure of Bearing Designations

A bearing designation generally consists of:

Bearing type code + dimension series code + bore code + suffixes

Example: 6206-2RS-C3

6: Deep groove ball bearing

2: Dimension series

06: Bore diameter 30 mm

2RS: Double-sided rubber seals

C3: Greater than standard (C0) clearance

In engineering selection, suffixes are just as important as the basic bearing designation.

Basic Principles of Installation and Fits

The purpose of bearing fits is to prevent relative movement between rings and mating surfaces while controlling deformation and clearance variation.

Rings subjected to rotating loads usually require interference fits

Rings subjected to stationary loads may use clearance or transition fits

During installation, forces should never be transmitted through rolling elements, and impact, misalignment, and contamination must be strictly avoided.

Conclusion

Different bearing types emphasize different engineering functions. Bearing selection is not about choosing “the best” bearing, but about selecting the one that best matches specific operating conditions.

In engineering practice, clearly defining functional requirements, understanding the differences between bearing types, and applying design, selection, and usage within a unified standards framework are the fundamental prerequisites for reliable bearing operation.